When bubble tea operators face scaling challenges, the choice between milk tea powder, tea concentrate, and traditional brewing isn’t just operational—it’s fundamentally about ingredient science. Each method represents a different approach to preserving tea compounds, managing oxidation, and maintaining sensory consistency across thousands of servings. What started as a simple question of convenience has evolved into sophisticated ingredient technology that food scientists continue to refine.

The tea industry has invested decades in solving a deceptively complex problem: how do you capture the volatile aromatics, polyphenols, and sensory characteristics of freshly brewed tea in a format that survives storage, transportation, and reconstitution? The answer depends on understanding the molecular behavior of tea compounds under different processing conditions.

Understanding Tea Compound Stability

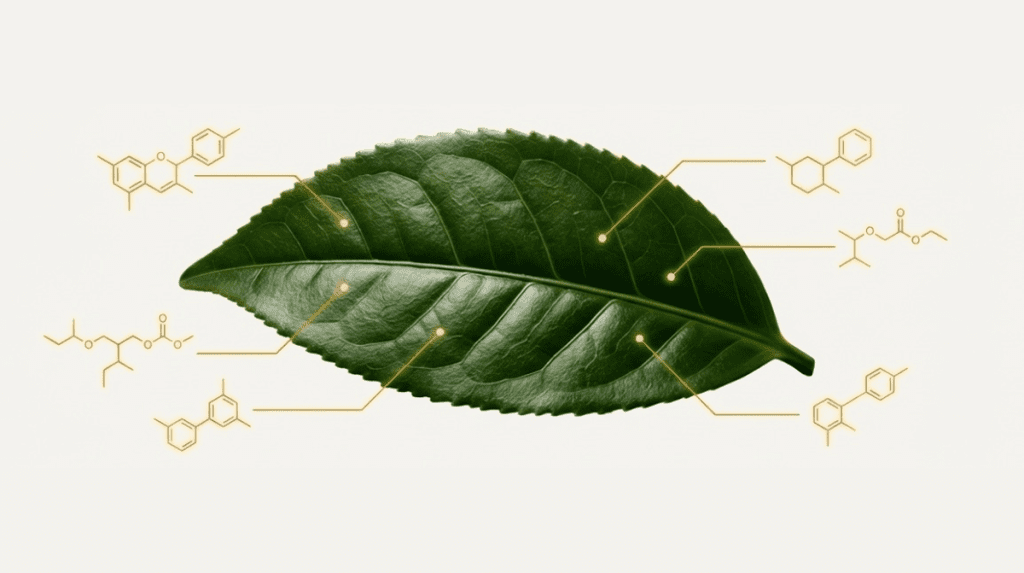

Tea’s flavor complexity comes from over 700 volatile compounds, including terpenes, aldehydes, and esters that create everything from floral notes to astringency. These compounds behave very differently depending on how they’re processed and stored. Fresh brewing extracts these compounds in real-time, but also starts oxidation immediately. Spray-dried powders lock compounds in place through rapid moisture removal, while concentrates use controlled extraction followed by preservation through refrigeration or aseptic processing.

The challenge becomes managing polyphenol oxidation—the same process that turns a cut apple brown. In tea, this oxidation affects both flavor stability and antioxidant retention. Research from the University of California, Davis demonstrates that different preparation methods show dramatically different polyphenol retention rates over time, with implications for both sensory quality and functional benefits.

What food scientists have learned is that there’s no universal “best” method. Instead, each approach optimizes different variables: fresh brewing maximizes initial flavor complexity, concentrates balance preservation with sensory fidelity, and powders prioritize shelf stability and operational simplicity. Understanding these trade-offs requires looking at the science behind each process.

Milk Tea Powder: Spray-Drying Technology

Milk tea powder represents one of the most technologically sophisticated approaches to tea ingredient development. The process typically involves brewing tea under controlled conditions, adding dairy solids and sweeteners, then spray-drying the mixture at temperatures between 160-220°C for just seconds. This rapid dehydration—pioneered in the dairy industry and adapted for tea applications—creates a stable powder with moisture content below 5%.

The science behind effective spray-drying lies in inlet and outlet temperature control. Too hot, and you degrade heat-sensitive compounds like catechins; too cool, and you get incomplete drying that leads to caking. Advanced spray-drying systems now use multi-stage drying with varying temperatures to optimize different compound classes. The result is a powder that, when properly formulated, can maintain sensory characteristics for 18-24 months at room temperature.

One limitation involves the Maillard reaction—the same browning reaction that gives bread its crust. During spray-drying, reducing sugars can react with amino acids, creating both desirable and sometimes off-flavors. Formulators manage this by carefully controlling sugar types and drying parameters, but it remains a key variable in powder quality. Companies like Kerry Group and Synergy Flavors have developed proprietary drying protocols that minimize Maillard reactions while maximizing compound retention.

From a formulation perspective, milk tea powders typically contain 40-60% carbohydrates (from added sugars and maltodextrin carriers), 15-25% dairy solids, and 5-15% tea solids, with the remainder being stabilizers, emulsifiers, and flavor compounds. The dairy component—whether from whole milk powder, non-fat dry milk, or dairy alternatives—significantly affects reconstitution behavior and mouthfeel.

Tea Concentrate: Extraction and Preservation Science

Tea concentrates take a different scientific approach: maximize extraction efficiency, then preserve the liquid through either refrigeration, aseptic processing, or controlled pH adjustment. The extraction process itself has become highly engineered, with variables including water temperature (typically 85-95°C for most tea types), extraction time (3-10 minutes), and tea-to-water ratio (often 1:20 to 1:40) all carefully optimized.

Advanced extraction systems now use counter-current extraction—where fresh water contacts already-extracted tea leaves first, then progressively less-extracted leaves—to maximize yield while minimizing over-extraction of bitter compounds. This process, adapted from the pharmaceutical industry, can increase extraction efficiency by 20-30% compared to simple steeping. The Tea Research Institute in Sri Lanka has published extensive research on optimal extraction parameters for different tea varieties.

Once extracted, concentrates face the challenge of microbial stability and oxidation control. Refrigerated concentrates (stored at 2-4°C) can maintain quality for 2-4 weeks, while aseptically processed concentrates—flash-heated to 135°C for seconds, then cooled and packaged in sterile conditions—achieve 6-12 month shelf life without refrigeration. Some manufacturers add natural preservatives like citric acid or ascorbic acid to extend stability, though this can affect final flavor profiles.

The concentrate format offers unique advantages for functional ingredient incorporation. Because you’re working with a liquid system, it’s easier to add fat-soluble flavors, emulsified fats for creaminess, or functional ingredients like MCT oil without the dissolution challenges that powders face. However, this same liquid format creates logistical challenges: concentrates require cold chain management and have higher transportation costs due to water weight.

Fresh Brewing: Real-Time Extraction Chemistry

Traditional brewing remains the gold standard for flavor complexity, primarily because it preserves volatile compounds that degrade during processing. When you brew tea fresh, you’re extracting compounds in their native state, including delicate floral terpenes and aldehydes that give high-quality teas their distinctive character. These compounds, which can represent up to 0.03% of tea’s dry weight, are disproportionately important to perceived quality.

The science of optimal brewing has been studied extensively, particularly in the specialty tea community. Water chemistry matters significantly: alkaline water (pH above 7.5) can lead to excessive tannin extraction and astringency, while very soft water may under-extract. Research from Cornell University shows that water hardness between 50-150 ppm produces optimal extraction for most tea types, though preferences vary by tea origin and processing method.

Temperature control is equally critical. Green teas generally extract optimally at 75-85°C to preserve catechins and minimize bitterness, while black teas benefit from 90-95°C to fully extract theaflavins and thearubigins—the oxidized polyphenols that give black tea its characteristic color and body. Automated brewing systems from companies like Curtis and Bunn now offer precise temperature and time control, reducing human variability.

However, fresh brewing presents significant operational challenges at scale. Beyond the equipment and labor requirements, there’s the consistency challenge: achieving identical results across multiple locations and operators requires extensive training and quality control. Tea quality itself varies by harvest, season, and storage conditions, introducing another variable. This is why many high-volume operations move toward standardized formats despite the potential quality trade-offs.

Comparative Analysis: Performance Metrics

To understand how these methods compare across critical performance dimensions, we need to examine both sensory and functional characteristics:

| Performance Metric | Milk Tea Powder | Tea Concentrate | Fresh Brewing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shelf Stability (months) | 18-24 (ambient) | 6-12 (aseptic) / 0.5-1 (refrigerated) | N/A (immediate use) |

| Preparation Time | 30-60 seconds | 60-90 seconds | 5-10 minutes |

| Labor Intensity | Low | Low-Medium | High |

| Initial Investment | Low ($500-2,000) | Medium ($2,000-8,000) | Medium-High ($3,000-15,000) |

| Flavor Complexity | Moderate | High | Highest |

| Batch Consistency | Highest | High | Moderate |

| Customization Flexibility | Low | Medium | Highest |

| Cold Chain Required | No | Yes (most types) | No |

| Polyphenol Retention | 60-75% | 75-90% | 100% (baseline) |

The data reveals why ingredient selection becomes a strategic decision rather than a simple cost calculation. A powder’s superior consistency and shelf stability come at the expense of flavor complexity and customization options. Concentrates occupy the middle ground, offering better sensory fidelity than powders while maintaining operational advantages over fresh brewing.

Quality Control and Consistency Considerations

From a food safety and quality perspective, each method presents different control points. Powders benefit from low water activity (typically below 0.3), which inhibits microbial growth and enzyme activity. This makes them inherently stable but requires careful attention to packaging integrity and humidity exposure during storage. The industry standard is metallized polyethylene bags with nitrogen flushing to prevent oxidation, though some premium powders use individual-serve sachets for maximum protection.

Concentrates require more rigorous microbial monitoring due to their high water activity. Aseptic processing achieves commercial sterility, but any post-processing contamination—through dispensing systems, for example—can lead to spoilage. Regular ATP testing and microbial swabbing of dispensing equipment becomes essential. Companies like Cargill offer antimicrobial additives that provide additional protection without affecting flavor, though these require regulatory approval in specific markets.

Fresh brewing introduces the variable of tea leaf quality control. Beyond basic food safety concerns (pesticide residues, heavy metals), there’s significant sensory variation based on tea grade, harvest timing, and post-harvest handling. Operators using fresh brewing typically establish supplier relationships with quality guarantees and conduct incoming sensory evaluations. Some high-volume operations now use spectrophotometry to verify tea extract color and strength, ensuring consistency across batches.

Formulation Flexibility and Innovation

The three methods offer vastly different platforms for product innovation. Powders excel at standardization but struggle with novel texture or flavor layer incorporation. Adding tapioca starch for increased viscosity or natural colorants for visual appeal is straightforward, but achieving “fresh-brewed” complexity remains challenging. Recent developments in encapsulation technology are changing this—microencapsulated flavor compounds can survive spray-drying and release during reconstitution, though this adds cost.

Concentrates provide the most flexibility for functional ingredient incorporation. Want to add collagen peptides for protein enrichment? Blend them into the concentrate. Looking to incorporate adaptogens like ashwagandha or rhodiola? The liquid format facilitates dispersion. This has made concentrates particularly popular in the functional beverage segment, where ingredient synergy and bioavailability matter.

Fresh brewing offers ultimate customization but requires more technical skill. Want to blend two tea varieties for unique flavor profiles? Experiment with fermented tea ingredients? Add osmanthus flowers or rosehips during brewing? Fresh systems accommodate these innovations easily, though they also require operator training and careful documentation to maintain consistency.

Sustainability and Environmental Considerations

Environmental impact is increasingly influencing ingredient selection, with each method presenting different sustainability profiles. Powders offer advantages in transportation efficiency—no water weight means lower fuel consumption and carbon emissions. However, spray-drying is energy-intensive, and the aluminum-laminated packaging materials can be challenging to recycle.

Concentrates carry water weight, increasing transportation impact, but modern aseptic processing has become increasingly energy-efficient. The Tetra Pak aseptic cartons commonly used for concentrates now offer recyclable options in many markets, though recycling infrastructure remains limited in some regions. Cold chain requirements add energy consumption for refrigerated varieties.

Fresh brewing eliminates processing energy but introduces waste considerations. Tea leaves create organic waste (though composting options exist), and water consumption during brewing and cleaning can be significant. According to data from the Water Footprint Network, tea production and brewing combined can require 30-50 liters of water per kilogram of prepared beverage, though this varies significantly by tea type and preparation method.

Regulatory and Labeling Implications

From a regulatory standpoint, each format navigates different requirements. Powders must comply with FDA regulations for dried dairy products, particularly around milk powder specifications if dairy is included. Clean label trends have pushed manufacturers toward simpler ingredient declarations, though functional requirements for flow agents, anti-caking compounds, and emulsifiers often necessitate additives. Natural alternatives like sunflower lecithin or organic tapioca maltodextrin help address clean label concerns.

Concentrates face different labeling considerations, particularly around preservative usage. Even natural preservatives like citric acid must be declared, and “preservative-free” claims require either aseptic processing or refrigeration disclaimers. The GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status of ingredients becomes important when formulating concentrates for extended shelf life.

Fresh brewing offers the simplest ingredient declaration—often just “tea” or “tea leaves”—but faces preparation and holding time disclosures if health departments require posting when the tea was brewed. Some jurisdictions mandate cold-holding requirements if brewed tea is stored longer than specific timeframes, typically 4 hours at room temperature or 24 hours refrigerated.

Cost Analysis and Operational Economics

Understanding the true cost requires examining both ingredient and operational factors. Powders typically cost $8-25 per kilogram depending on quality and formulation, with yields of 50-100 servings per kilogram at typical dilution rates. The low labor requirement (30 seconds per serving) and zero cold chain costs offset higher per-unit ingredient costs, particularly at high volume.

Concentrates range from $15-40 per liter concentrate, yielding 20-40 prepared beverages depending on dilution. Cold chain management adds approximately $0.10-0.25 per serving in refrigeration and logistics costs for refrigerated varieties, while aseptic concentrates eliminate this but cost 20-30% more initially. Labor costs remain low at 60-90 seconds per serving.

Fresh brewing presents the most complex cost structure. Quality tea leaves range from $20-80 per kilogram, with yields of 30-50 servings per kilogram. However, labor costs—typically 5-10 minutes per batch plus periodic rebrewing—can exceed ingredient costs at lower volumes. Equipment investment ($3,000-15,000 for commercial brewing systems) and maintenance add capital and operational expenses. The National Restaurant Association estimates total cost-per-serving for fresh-brewed beverages at $0.40-1.20 depending on tea quality and operational efficiency.

Making the Strategic Choice

The optimal selection ultimately depends on operational priorities and business model. High-volume quick-service operations often favor powders for their consistency, shelf stability, and operational simplicity—when you’re producing 500+ beverages daily, preparation efficiency and batch-to-batch consistency become paramount. This is why chains like Kung Fu Tea and Gong Cha have standardized on powder-based systems for core menu items, though many offer fresh-brewed premium options.

Mid-volume operations with cold chain infrastructure increasingly adopt concentrate systems, particularly when menu differentiation matters. The improved flavor fidelity and functional ingredient flexibility justify the added logistics complexity. Concentrate systems also shine in catering and event applications where preparation speed matters but fresh-brewing infrastructure isn’t practical.

Fresh brewing remains the choice for specialty tea houses, premium café concepts, and operations where tea quality is a core brand differentiator. The sensory superiority and customization flexibility justify the operational complexity for customers willing to wait—and pay—for premium quality. Some operators adopt hybrid approaches: fresh-brewing for signature items while using concentrates or powders for high-volume basics.

What food scientists continue working on is narrowing the quality gap. Next-generation spray-drying techniques like freeze-drying under vacuum offer better volatile retention, though at higher cost. Novel extraction methods including supercritical CO2 extraction capture a wider range of tea compounds for premium concentrates. Encapsulation technologies allow powder formulators to recreate complexity that previously required fresh brewing.

The technology trajectory suggests that processed formats will continue improving in quality while fresh brewing systems become more automated and consistent. However, the fundamental trade-offs between shelf stability, operational efficiency, and sensory excellence will likely persist. Understanding these trade-offs from an ingredient science perspective—not just an operational one—helps operators make informed decisions that align with their specific brand positioning and operational capabilities.

FAQ

Milk tea powder offers the longest shelf life at 18-24 months under ambient storage, achieved through spray-drying that reduces water activity below 5%, inhibiting microbial growth and enzyme activity. Tea concentrates require refrigeration for 2-4 weeks or aseptic processing for 6-12 months shelf life. Fresh brewing requires immediate consumption with no storage capability. Selection depends on operational scale, cold chain infrastructure, and inventory management capacity. High-volume chains typically favor powders to minimize logistics costs and maximize operational flexibility.

Milk tea powder costs $8-25/kg, yielding 50-100 servings with minimal labor at 30 seconds per serving. Tea concentrate ranges $15-40/liter for 20-40 servings, adding $0.10-0.25/serving for cold chain management. Fresh brewing costs $20-80/kg for 30-50 servings but requires 5-10 minutes per batch and $3,000-15,000 equipment investment. High-volume operations favor powders for cost efficiency and consistency. Premium tea houses choose fresh brewing to justify higher pricing through quality differentiation and artisanal positioning.

Fresh brewing retains 100% baseline polyphenol content, including complete catechins, theaflavins, and antioxidant compounds. Tea concentrates preserve 75-90% through controlled extraction and aseptic processing, superior to powder’s 60-75% retention. Spray-drying, while rapidly locking compounds, causes partial degradation of heat-sensitive components during high-temperature processing. Brands emphasizing functional health benefits should select concentrates or fresh brewing systems, supported by third-party testing certification for polyphenol content validation and consumer transparency.

Milk tea powder delivers highest consistency through standardized formulation ensuring batch-to-batch flavor stability. Tea concentrates require ATP testing and microbial swabbing to monitor dispensing system contamination risks. Fresh brewing shows highest variability, requiring strict SOPs controlling water temperature (green tea 75-85°C, black tea 90-95°C), steeping time, and tea grade. Implement spectrophotometry to verify extract color and strength. Multi-location operations should adopt central kitchen systems or standardized premix products.

Milk tea powder excels in transportation efficiency with no water weight reducing carbon emissions, but spray-drying consumes significant energy and packaging materials challenge recycling. Tea concentrates carry water weight increasing transportation carbon footprint with higher cold chain energy consumption, though modern aseptic packaging improves recyclability. Fresh brewing generates compostable tea leaf waste but requires 30-50 liters water per beverage unit, creating substantial water footprint. Recommend life cycle assessment (LCA) integration considering raw material sourcing, transportation distance, and end-of-life disposal.

Sources & References

- Cornell University Food Science Department — Tea extraction and brewing research

- University of California, Davis Food Science — Polyphenol stability and oxidation studies

- Institute of Food Technologists (IFT) — Food processing and ingredient technology

- FDA Food Safety and Applied Nutrition — Regulatory framework for tea products

- Tea Research Institute, Sri Lanka — Tea processing and extraction science

- Water Footprint Network — Environmental sustainability data

About the Author

Dr. Mei-Lin Chen is Senior R&D Scientist at YenChuan, where she leads ingredient innovation for bubble tea applications. With a Ph.D. in Food Science from UC Davis and 12 years of experience in beverage formulation, she specializes in translating complex food science into practical product development solutions. What fascinates her most about tea ingredient technology is how recent advances in processing have made it possible to deliver authentic flavor experiences at scale—something that seemed impossible when she started her career. Dr. Chen has published research on polyphenol stability and natural preservation systems in peer-reviewed journals.

Connect with the YenChuan team on LinkedIn.

Ready to Elevate Your Bubble Tea Ingredient Strategy?

Whether you’re optimizing for consistency, flavor quality, or operational efficiency, choosing the right tea format requires understanding both the science and your specific business needs. YenChuan offers all three formats—premium milk tea powders, concentrated tea extracts, and traditional loose-leaf selections—plus the technical expertise to help you select the optimal solution for your operation.

Let’s discuss your ingredient requirements and formulation goals. Our food scientists can help you evaluate options based on your volume, brand positioning, and quality standards.